After more than two hours of skimming over impossibly blue waves, about 17 miles off the Hawaiian island of Kauai, the time has finally arrived. Our boat is closing in on Niihau, the Forbidden Island, whose arid flanks slope dramatically skyward and call to mind a flat-top haircut.

We won’t be allowed to set foot on the enigmatic Hawaiian island, as strict policies guard this privately owned soil from most visitors, but the plan is to scuba dive very near it. Just beyond its shores, we’ll glide over seamounts and through lava formations, alongside big sharks and — if we’re lucky — endangered Hawaiian monk seals. In between dives, though, we’ll have clear views of the island itself. Maybe we’ll even catch a glimpse of the inhabitants.

A few dozen Hawaiians live on Niihau in much the same way their ancestors did. There are also populations of aoudad and eland — African game that trophy hunters helicopter in to kill. The trips are wildly expensive, but once you’ve heard the story of Niihau, it begins to feel worth it.

Niihau’s origins

Like the rest of the archipelago, the island formed when a hot spot beneath the sea spewed molten lava that became new land, about 6 million years ago. Apparently, the island was a whole lot bigger back then, but about 5 million years ago, most of it collapsed. Left behind were Niihau and a smaller neighbor Lehua, a crescent-shaped volcanic cone frequented by seabirds.

Niihau’s first people were the ancestors of seafaring Polynesians who arrived in double-hulled sailing canoes. They were ruled by Hawaiian nobility, and the island’s coveted shells are named for its first leader, Kahelelani, who was born in the early 17th century. In 1864, King Kamehameha IV sold Niihau to Elizabeth Sinclair, a Scottish plantation owner, for $10,000 in gold. Part of the agreement was that Sinclair would preserve the culture and traditions, and her descendants who now own the island but do not reside there — the Robinson family — continue to honor that agreement.

To this day, only Native Hawaiians are allowed to live on the island, and Niihau is the only place on Earth where Hawaiian is the primary language. There are no paved roads, no internet or telephone services, no running water, and no power lines, although solar panels do provide electricity.

Visitors are limited to members of the Robinson family, invited guests of residents, and a small number of tourists who book private helicopter and hunting tours run by the Robinson family’s company. According to the company website, helicopter tours cost $630 per person, with a minimum of five people (so, $3,150 minimum), and the hunting tours start at $3,300 per person.

Killing an aoudad (an African goat) entails a trophy fee of $2,700, on top of the hunting fee of $3,300 per day. If you want to kill an eland (the world’s largest antelope), the trophy fee is $3,700.

“I heard no one is allowed to take any photos on the tours,” one of the divemasters told me as we zipped toward the island. Others who had read or heard about the island chimed in with more rumors, but everyone agreed that getting accurate information about what goes on around Niihau is almost impossible.

There has been at least one violation of the visitor rule. In 1941, a Japanese pilot crash-landed on the island after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, setting off a series of events known as the Niihau Incident, which has been retold in books, on film and on this website. The story ends with one local bashing the pilot’s head in with a rock, another dying by suicide and two more being sent to concentration camps.

The closest I’ll get to Niihau

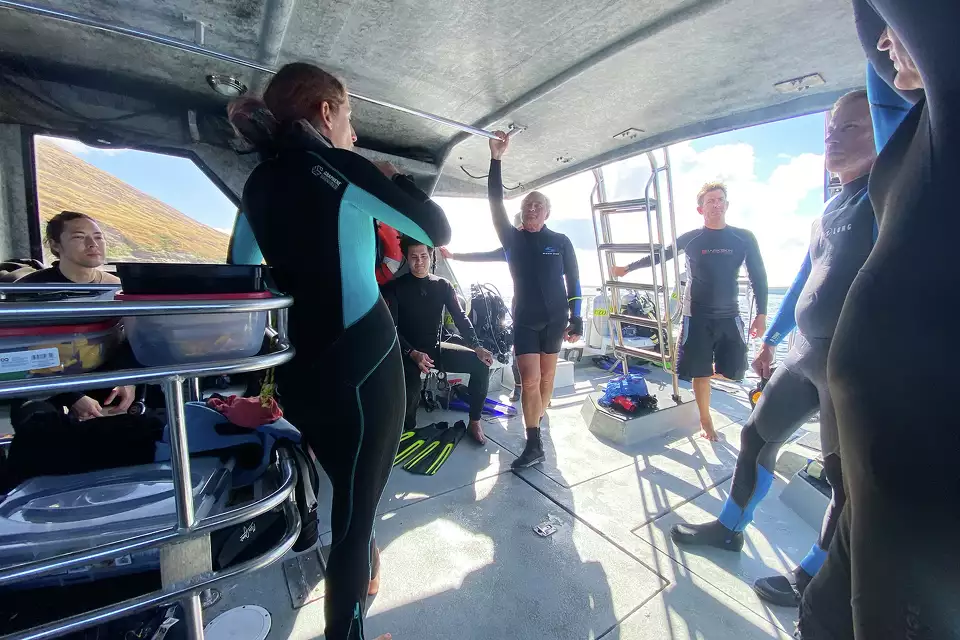

To know about Niihau is to want to go to Niihau, or to get as close as possible anyway. For those who can’t afford to spend thousands of dollars on a helicopter ride or safari, the only option left is to take a boat. A few companies run snorkel and diving trips nearby, and I went with Seasport Divers, a longstanding and reputable outfitter with a big, luxurious dive boat. I was in luck, because during my trip to Kauai, the company would be running its final Niihau trip of the season. (Come October, rougher seas often make the crossings unbearable.)

Everyone on the boat had logged at least 30 dives, as extensive experience is required for the Niihau trip. Most people had advanced certifications, and some even worked as divemasters for other Kauai dive shops. Turns out, pretty much any serious diver jumps at the opportunity to go to Niihau, where the combination of dramatic underwater topography, big pelagic animals and unusual little creatures makes for an unforgettable day.

As we prep for our first dive and receive the safety briefing, my gaze keeps drifting to the islands, which look nothing like verdant Kauai. Because Kauai’s mountains capture most of the region’s rainfall, Niihau and Lehua are largely barren, and surrounding waters mostly undisturbed by sediment offer scuba divers superior visibility. As the first of the divers giant-strides off the boat, an endangered Hawaiian monk seal welcomes them to the depths.

The monk seal is one of only two endemic mammals in Hawaii, the other being the hoary bat. Thanks to threats such as habitat encroachment, marine debris, entanglement in fishing nets and low genetic variation, there are only around 1,570 of these seals left in the world, and remote, sparsely populated Niihau offers travelers the best chance of seeing one.

I end up being one of the last people off the boat, and by the time I reach the bottom, the seal has already taken off. At around 80 feet, our group of five divers begins to explore massive, eroded lava formations brimming with marine life. When there isn’t a big, circling sandbar shark capturing my attention, the divemaster is pointing out colorful endemic fish species and sea slugs, or we are gliding down a massive seawall alongside a “fish fall” teeming with rare pyramid butterflyfish. On the second dive, we drift through jagged lava tubes and beneath stunning archways, encountering the occasional green turtle, toothy eel or big school of fish.

Back on the surface, we take a little joyride around Lehua. As we circumnavigate, a group of spinner dolphins begins leaping in our wake, and graceful booby birds soar over the boat. Waves crash against the cone-shaped island, and white water explodes around the base, making a loud but soothing whoosh. The captain slows the boat as we approach a formation dubbed Keyhole Cave, a narrow opening between two rocks, with a bridge at the top. Sometimes it’s possible to get closer, he tells me, but the conditions are a bit dicey.

During lunch, divers compare notes on what they’ve seen beneath the water. Despite my frequent glances over at Niihau, no signs of life appear. The inhabitants are sometimes spotted at the beach gathering Kahelelani shells, a divemaster tells me, but not today.

I find myself idly considering what might happen if I were to get separated from the group and wash up on the island. It’s not something I’m seriously considering, of course. My curiosity about Niihau will have to go unquenched, this time, though the consolation prize is pretty remarkable.

At the start of my third dive, I find a monk seal resting on the bottom. It looks so relaxed, so at home in this strange and isolated place. For now, I decide, that’s probably the most important thing I need to know about Niihau.

Source : SFGATE