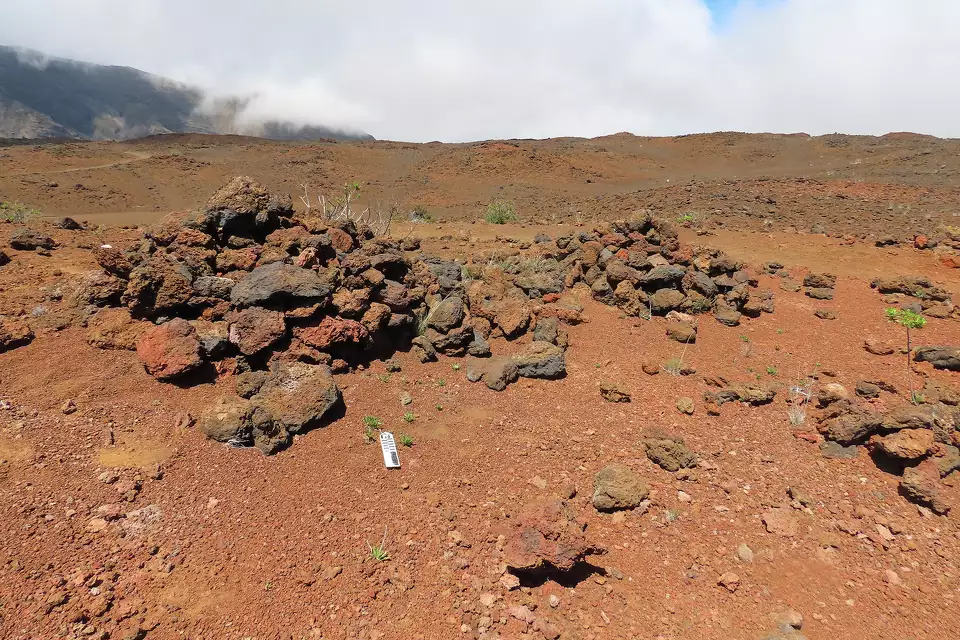

It’s illegal to take anything from a national park — it doesn’t matter if it’s a grain of sand or a pine cone. But every year, visitors to Hawaii have been picking up lava rocks as souvenirs and mailing them back, once they hear of a myth that bad luck will befall them.

In 2017, Haleakala National Park on Maui received 1,275 rocks in the mail, often accompanied by a letter of apology with a description of the thief’s misfortune — and not much has changed since then.

“We would love for people just to stop taking stuff and then also please just stop mailing us stuff,” Heather Whitesides, a public affairs officer for Haleakala National Park, tells SFGATE.

“These rocks that are mailed back to us can have pretty horrific invasive species,” she continues. “We do a really great job of trying to protect our island, from species coming in and all these different intruders, and so when people freely mail back all of these items, of which the majority don’t even belong here [at Haleakala National Park], it actually does take a lot more time and causes significant issues.”

The bad-luck story centers around Pele, the goddess of Hawaii’s volcanoes, who lives at the Halemaumau crater in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, where the Kilauea volcano is active. She’s embodied in all of Hawaii’s volcanoes, however, including in the black sand beaches (which are made from lava hitting the ocean) and lava rocks.

The origin of the myth is a mystery though. Whitesides says there are no records, documentation or cultural history that supports the idea that taking a lava rock will bring bad luck. She’d also like to see the narrative change from placing blame and negative connotations on Pele, who is revered by Native Hawaiians.

The late Herb Kane, acclaimed artist and Hawaiian historian, wrote in his book, “Pele: Goddess of Hawaii’s Volcanoes,” that it’s possible the belief grew from confrontations between missionaries, who condemned Hawaii’s customs, and Native Hawaiians, who respected the goddess. Or it could have been made up by modern-day tour guides, who wanted visitors to stop littering in their vehicles.

No one knows the answer, but it shouldn’t take a curse to realize that taking from someone’s home is a form of disrespect.

“Hawaii is a special place to the people that call this place home, and they open up the doors to the world so that everyone can experience this place as well,” Katie Matthew, museum curator for Haleakala National Park, tells SFGATE. “So yeah, in a way, to respect the people that live here and call this place home, and think about, this is their home, this is all we have. If everyone were to take everything off this island, it would be gone.”

It’s not just a rock

Aside from their connection with Pele, Hawaii’s rocks are important for other reasons. Taking rocks or even stacking rocks is strongly discouraged by the park, as it could destroy historic sites or disturb native species.

“The rocks here are home to a lot of our native, rare and endangered species, like the uau, which is a Hawaiian petrel. We also have small insects that are only found at the summit of Haleakala, like the flightless moth and the native wolf spider,” Matthew says.

The summit of Haleakala is considered a sacred space by Native Hawaiians, and archaeological remains are also still standing — and not always marked with a sign. Hawaii’s culture is lithic, meaning many of its stones were used historically by Native Hawaiians for tools and structures such as houses, temples and walls. Carved stones could represent other gods, and ahu, or cairns, were used as shrines for ceremonial purposes and as boundary markers.

“You can have a lot of archaeological sites that are just made out of stacked stone, and people just don’t realize they are archaeological sites and they could be disturbing these sites,” Matthew says.

Visitors, documenting their trips to the Hawaiian Islands by traipsing off boardwalks, over guardrails and off trails, should rethink their actions and the consequences.

“We see resource damage across the board, and we’re doing our best to, one, inform our visitors why we want them to stay on trail, why we’d like them to take pictures, not objects,” Whitesides says, “but also we really want these resources to be here for generations and then also to protect the culture and also the stories of Native Hawaiians as well.”

Source : SFGATE