Just before sunset on one of Hawaii’s premier stretches of beach, a sea turtle drags itself out of the surf and onto the sand to bask, as humans sunbathe and frolic nearby. A handful of people gather around the scaly, prehistoric-looking reptile, who naps peacefully despite the audience.

When a second turtle drifts into the shallow cove, it prompts squeals of excitement from the crowd. Then comes another. And another. And another.

Soon, about a dozen Hawaiian green sea turtles — known as honu in Hawaiian — have scooted ashore and fallen asleep on Poipu Beach, a popular tourist spot on the island of Kauai. In response, a team of volunteers get to work, setting up safety cones and signage to keep back the semi-circle of onlookers sipping cocktails and snapping photos from 10 feet away. That’s as close as the public is legally allowed to get to green sea turtles, thanks to their status as a threatened species.

While someone plays “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” on a speaker, a small child darts away from his mother and runs giggling through the turtles.

“Oh, oh, oh, oh! No, no, no, no!” a volunteer cries, and the embarrassed parent reclaims her son.

The turtles snooze through the drama, seemingly accustomed to the hubbub their presence now elicits on Poipu Beach every single night. And yet, until two years ago, sea turtles rarely came ashore on this beach.

Rampant overfishing reduced the population significantly in the mid-1900s; the few turtles left shied away from humans and the beaches they frequented most. But the population has slowly rebounded after environmental protections were enacted in the 1970s. In the 1990s, turtles began coming ashore to rest on beaches across the Hawaiian Islands, including some often frequented by people, such as Oahu’s Laniakea.

Two years ago, around when the pandemic led to the closure of many beaches, turtles began coming ashore here at Poipu Beach, one of the most visited beaches on Kauai. The phenomenon hasn’t stopped since restrictions were lifted, leading to the nightly ballet between eager tourists and volunteer protectors, who keep a watchful eye over as many as 100 turtles a night, the first time anyone can remember a time when turtles have arrived in these numbers, each and every night, on such a popular beach.

How to manage such a spectacular event is anything but clear, and people are pretty much losing their minds over it.

“We haven’t had to navigate this before,” says Debbie Herrera, volunteer and education coordinator of Malama i na honu, the nonprofit group that organizes volunteer turtle protectors to watch over beaches on Oahu and Kauai. “Everyone is learning as we go.”

How the basking sea turtles started

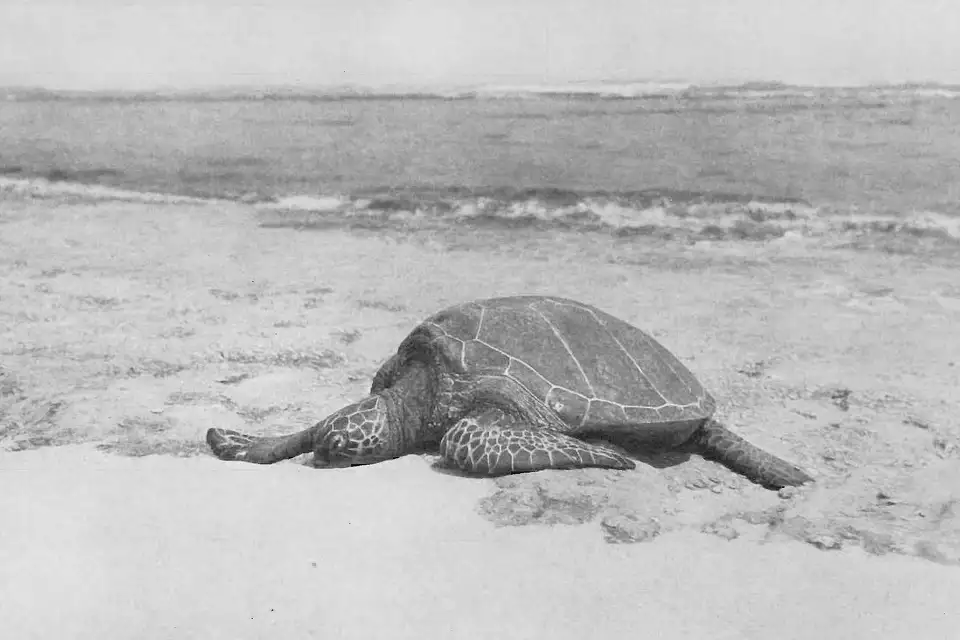

The first published photo of a Hawaiian green turtle basking on a beach appeared in National Geographic Magazine in 1925. The caption read: “These grotesque creatures browse in submarine fields of algae until hunger is satisfied, and then crawl heavily out to sprawl in the sand, safe from enemies in the sea.”

Basking behavior among sea turtles is not fully understood, but that explanation is a pretty decent one, says sea turtle scientist George Balazs, who worked at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for almost half a century.

When Balazs began studying Hawaiian sea turtles in the early ’70s, he traveled to where the Nat Geo photo was taken, the French Frigate Shoals. The uninhabited islands are on the northwestern side of the Hawaiian archipelago, more than 500 miles from Kauai, and this is where Hawaiian green sea turtles typically come to lay their eggs. Although the turtles could often be seen basking on beaches around their nesting grounds, no records existed of them basking on inhabited Hawaiian Islands when Balazs began his work.

Through his research, he discovered that turtles were being overharvested by commercial fishermen. They were understandably afraid of humans, Balazs told me, and didn’t dare swim ashore on Hawaii’s inhabited islands. An ensnared 100-pound turtle fetched about $100 in the ’70s, he said, and the meat often landed in fancy restaurant dishes across the islands.

Sea turtles had long been sacred to Native Hawaiians. When Balazs’ research showed a dramatic population decline — he documented a mere 67 sea turtles returning to their nesting grounds in 1973 — people rallied around the cause. In 1975, the state government banned the commercial harvest of sea turtles in Hawaii, and in 1978, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and NOAA listed the Hawaiian green sea turtle as threatened, triggering protections against harassment, including the 10-foot rule. Their numbers began to recover rapidly, with the population growing at an average of about 5% per year, according to Balazs.

“The speed that the numbers recovered after the commercial fishing was absolutely shocking to me,” Balaszs told me.

Over time, the turtles seemed to lose their fear of humans. In the 1990s, something magnificent began to happen: The sea turtles started crawling out of the sea and resting on inhabited island beaches across Hawaii. One in particular — Oahu’s Laniakea Beach — got famous for it.

How Hawaiian turtles became a tourist attraction

In March of 1999, a solitary green turtle began hauling itself out of the ocean and onto the vanilla-colored sands of Laniakea. The locals started calling him Brutus.

Herrera, the volunteer coordinator, distinctly remembers visiting the North Shore with her kids around that time and seeing Brutus. There weren’t many visitors at Laniakea Beach back then, she says, just some surfers and fishers. Although she had been living on the island for a couple of years, she had never seen a turtle crawl out of the water and onto the sand.

“I called the Humane Society and I said, ‘There’s a turtle that I think is dead on the beach,’” Herrera says.

She was a schoolteacher then, with no background in marine science or turtle biology. She was aware that sea turtles came ashore to lay eggs on beaches, but like most people, she had no idea that they sometimes bask on land.

Of the seven species of sea turtles, only green turtles emerge from the water to bask. The phenomenon has been documented in just four places: the Galapagos, Socorro Island, Australia’s Wellesley Islands and the Hawaiian archipelago. After Brutus hauled out at Laniakea, more turtles followed. By 2005, 16 resident turtles were showing up regularly to bask. People also began to arrive in greater numbers, until tour buses were bringing hundreds of visitors a day. Some started calling Laniakea “Turtle Beach.” Some of those visitors would move in closer than 10 feet to the turtles, touching or even sitting on them.

Those interactions led Balazs, then the head of marine turtle research for the NOAA, to spearhead the “Show Turtles Aloha” campaign, which aimed to teach people about the turtles and minimize negative impacts on the animals. That work eventually turned into the nonprofit Malama i na honu, whose volunteers have been working daytime shifts and collecting data on Laniakea’s turtles since 2007, tracking anywhere from 500 to 1,200 instances of turtles basking on the beach per year.

Tourists coming to see the turtles on Laniakea have created significant conflict, including gridlock from people parking illegally, which infuriated locals call “turtle traffic.” At least one crash has occurred, involving a 10-year-old pedestrian on an increasingly busy thoroughfare.

In 2021, when turtles began turning up on Poipu Beach, the Kauai community reached out to Malama i na honu to ask if the nonprofit could establish a volunteer program on Poipu Beach. But Herrera — who started volunteering with Malama i na honu in 2013, and has served as volunteer and education coordinator for the last 10 years — had her hands full at Laniakea. Her first response, she told me, was “absolutely not.”

Still, she flew over to Kauai to assess the situation, and couldn’t believe the sheer numbers of turtles that were crawling out of the sea to sleep on Poipu Beach every night. She knew something had to be done.

“Like you and everyone else,” she told me, “I was flabbergasted.”

The problems with Poipu

On Poipu Beach, the sun has set behind the Pacific. But hundreds of visitors still linger, snapping photos and swimming in the ocean right where the turtles are waiting for a chance to come ashore.

A volunteer in a cowgirl hat picks up her skirt and wades into the water. “At low tide, this is the hallway to their bedroom,” the volunteer explains to the swimmers. “Can we open up the door so they can come in and sleep?”

The swimmers comply, perhaps because they’ve been asked so nicely. That’s always the goal, Herrera tells me: not just to redirect people who are interfering with the turtles’ behavior, but to do it in a friendly, approachable way.

That isn’t always easy; volunteers have dealt with turtles being chased, straddled and scared off more times than they can count. It hasn’t helped that people have continuously posted photos and videos on social media, Herrera told me, which has led to the event growing ever more popular.

The crowds have created a trash problem, left bathrooms in unsanitary conditions and eroded a nearby bluff, Herrera added. And in truth, the volunteers don’t have very much authority. People are allowed to swim at Poipu Beach. People are allowed to fish. Although technically the volunteers could report visitors who refuse to remain 10 feet away from the turtles, that’s not the purpose of the program.

If Herrera had her way, Kauai County would close the beach to visitors at night, giving it over to the turtles and local fishers, although there’s been no indication from that agency or any other that a beach closure is a possibility. (The county did not answer SFGATE’s inquiries about a possible closure.)

There is some evidence, though, that community leaders are starting to shift how they think about Poipu Beach. For instance, the Poipu Beach Foundation recently canceled its New Year’s fireworks show to avoid harassing the turtles, according to Sue Kanoho, executive director of Kauai Visitors Bureau.

There’s also an unspoken rule in Kauai that businesses will not promote the turtles as a tourist attraction, Kanoho told me, emphasizing the need to protect the wildlife. To that end, the bureau is planning a wildlife summit in January to ensure that Kauai’s tourism professionals are clear on the rules around endangered species.

In the meantime, the volunteers of Malama i na honu will continue monitoring Poipu Beach each night, making gentle suggestions that people move back, adjusting safety cones as necessary, and teaching people how to take nighttime iPhone photos without using any flash. They will answer question after question, for as many hours as it takes, until visitors leave the beach for the night.

Inevitably, more people will come. And with any luck, so will more turtles. The hope is that Poipu, and all the other beaches where turtles have chosen to bask, can accommodate both.

“It’s about co-existing,” Herrera says. “I love the idea of people coming down and seeing it, because it’s amazing. It’s phenomenal. It’s beautiful. It’s all of those things. But when they walk away, I want to see it continue.”

Source : SFGATE